First IronMQ impressions

First time I touched messaging was in the first few years of my professional life working on software that supported fire departments in their day-to-day activities. The dispatching software would send messages to a proprietary broker, which in its turn would forward them to interested subscribers; other dispatching clients, or services. To ensure availability, the broker component could failover to a different machine, but that was about it. It didn’t allow you to queue or retry messages; if you weren’t up when the messages were forwarded, you would never receive them. When the brokers were both down, all messages would be lost; the clients didn’t have infrastructure out-of-the-box that could queue the messages locally until it came back up again. When things went haywire, and they occasionally did, these missing features would often leave us with an inconsistent state. More modern messaging software has solved these concerns though.

Although quite a few systems would benefit from asynchronous and loosely coupled messaging - especially to improve reliability and (perceived) performance, but also scalability, I still too seldom see or hear about projects that get to go that extra mile. Solutions often end up compromising in quality to avoid introducing that extra component and those unconventional questions. And this decision might be perfectly sound, because lots of factors are at play, not just technical ones. It’s still a pity when you see solutions struggle to solve a problem in a decent way because they’re stuck with synchronous communication.

Imagine a public website that’s in the business of booking hotels. The offers they show to their customers are all based on data provided by third parties. Because it’s so expensive to fetch this data, it’s being cached, and as a result, it’s stale seconds after fetching it. The moment a user confirms, they could fetch fresh data from the relevant third party to make sure the room is still available, but this process is error prone: the third party might be down, fetching the data is really slow, one of our their own components might be down, on conflicts they might want to compile a list of some decent alternatives, which in its turn might also be too slow if done on demand. One alternative could be to queue the booking, and process it in the back-end. Once they’re done processing it, they can mail the user a confirmation or an apology with a list of alternatives attached. By making this process asynchronous, they avoid the risk of a slow user experience and clumsy failures they can’t recover from, making them lose business in the long run. But then again, they also take the burden of extra infrastructure, new operational concerns and different questions. Trade-offs.

Anyways, in this blog post, I wanted to share some first impressions on IronMQ. I admittedly kind of accidentally discovered this service browsing through AppHarbor‘s add-ons. Here it is described as “a scalable cloud-based message queue”.

Basically IronMQ gives you a REST enabled queue in the cloud. After authenticating, you can POST a new message to the queue. If you are unable to POST the message, you’ll lose it, since there is no support out-of-the-box for retrying or persisting the message on the client. Once the message is posted, another process can GET the message, and DELETE it after successfully processing it. If something happened to go wrong while processing the message, the message will return to the queue, and be retried one minute later. If the message processing keeps failing on subsequent retries, the retries won’t repeat infinitely though; messages expire (the default is 7 days, and the maximum is 30 days). This is exactly the kind of infrastructure we need to support the asynchronous booking scenario: have the customer put its booking on the queue, and one of our background processes will try to process it; if something goes wrong, we’ll just keep retrying for a while.

The REST API is simple, yet there are client libraries available for most popular languages. They don’t provide that much extra functionality though. Here’s the gist.

var queue = new IronMQ(queueName, projectId, token);

queue.Push("{ hello: world }");

var message = queue.Get();

queue.Delete(message.Id);

In this scenario you’re responsible for pulling data from the queue. This is just one way to go at things though; another option is to let IronMQ push messages to your HTTP endpoints. While this allows you to outsource some infrastructure to their side, it raises other concerns:

- Security: you might need to enable HTTPS, and provide an authentication mechanism.

- Debugging: if you want to do some end-to-end integration testing on your local machine, you’ll need to give your machine a public IP and set up something like dyndns.

- Scalability: depending on the expected message volume, and the web stack you’re rolling with, it might be more expensive to have to set up all these web servers, instead of a few background workers.

Errors are handled quite elegantly; once you processed the message successfully, make your endpoint return HTTP status code 200 or 202, and the message will be removed from the queue. HTTP status code 202 is used for long running processes. If the response code is in the 400 or 500 range, the message will return to the queue to be retried later.

When the expected volume of messages is rather small, it makes more sense to opt for push; you don’t waste that many HTTP requests.

IronMQ makes it extremely simple to get started; go to their site, get a project id and a token, and start making HTTP calls. Do them yourself, or use one of the client API’s. But it also seems to be all you’re going to get; there is no infrastructure that addresses operational concerns, error queues, retry strategies, local queues,… IronMQ provides you with raw queueing infrastructure, not a framework.

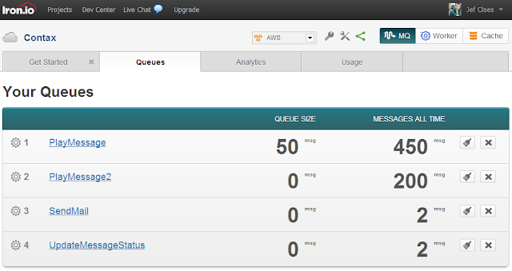

Their site does give you a look into your queues though; you can’t look at the messages, but you do get a nice overview.

I don’t mind that it’s not a turnkey solution though; I learn a lot from tinkering with this stuff. Solving problems and considering trade-offs for yourself is priceless.

Using HTTP for messaging still feels a bit quirky to me. As long as I can remember people have been making me believe HTTP is not the best fit for high-throughput messaging scenarios, and I do understand their motivations somewhat. But when even databases start to embrace HTTP, it’s probably time to shake off the doctrine. It’s so comfy to not have to understand a new protocol, and HTTP just seems such a sensible thing to do when you’re off-premise.

I’m going to conduct some more experiments this week, I’ll see what gives.