Some experimental infrastructure for IronMQ pull

I wrote about using IronMQ as a cloud-based message queue last week. In that post I explained that you can go at using IronMQ in two ways; either you pull from the queue yourself, or you let IronMQ push messages from the queue to your HTTP endpoints. At first sight, the latter allows you to outsource more infrastructure to their side, but upon closer inspection it also introduces other concerns: security, local debugging and scalability.

Out-of-the-box there is no infrastructure in the client libraries to facilitate periodic pull - polling, that’s why I took a stab at doing it myself. It’s still rough, not production tested, and hasn’t considered a bunch of niche scenarios, but it should give you an idea of the direction it’s going.

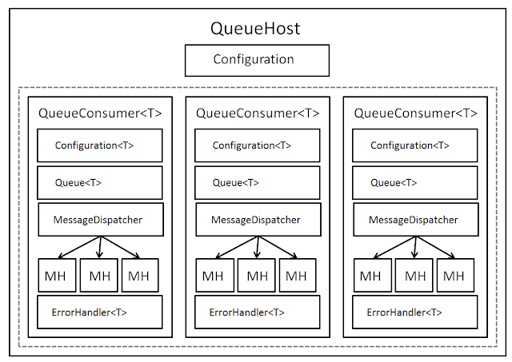

A high-level overview of the components looks like this.

A queue host hosts multiple queue consumers. Each queue consumer will poll a queue for one type of message on a configurable interval, and dispatch dequeued messages to relevant message handlers. After handling the message, the message will be deleted from the queue. If something happened to go wrong, the error handler for this type of message will be invoked, and the message will automatically return to the queue.

I’m going to look at each component, starting with the smallest, and slowly assemble them into bigger components.

Each queue consumer can be configured independently. For now, only the polling interval can be changed. By default it’s one second, or 1000 milliseconds.

public interface IQueueConsumerConfiguration<T>

{

int PollingInterval { get; }

}

public class QueueConsumerConfiguration<T> : IQueueConsumerConfiguration<T>

{

public int PollingInterval

{

get { return 1000; }

}

}

A queue can push messages, get raw messages, and delete them. The implementation makes use of the OSS IronIO client libraries.

public interface IQueue<T>

{

bool TryGet(out Message message);

void Delete(string messageId);

void Push(T message);

}

public class Queue<T> : IQueue<T>

{

private readonly IronIO.IronMQ _queue;

public Queue(string projectId, string token)

{

Guard.ForEmptyString(projectId, "projectId");

Guard.ForEmptyString(token, "token");

var queueName = typeof(T).Name;

_queue = new IronMQ(queueName, projectId, token);

}

public bool TryGet(out Message message)

{

message = _queue.Get();

return message != null;

}

public void Delete(string messageId)

{

Guard.ForNull(messageId, "messageId");

_queue.Delete(messageId);

}

public void Push(T message)

{

Guard.ForNull(message, "message");

_queue.Push(JsonConvert.SerializeObject(message));

}

}

A message dispatcher dispatches messages to the relevant handlers.

public interface IMessageDispatcher

{

void Dispatch<T>(T message);

}

public class MessageDispatcher : IMessageDispatcher

{

private readonly IKernel _kernel;

public MessageDispatcher(IKernel kernel)

{

_kernel = kernel;

}

public void Dispatch<T>(T message)

{

var handlers = _kernel.GetAll<IMessageHandler<T>>();

foreach (var handler in handlers)

handler.Handle(message);

}

}

If something goes wrong pulling the message from the queue or handling it, the error handler will be invoked passing in the exception and the raw message. Since it’s possible that something is wrong with the message in itself, I pass in the raw message with the serialized message and all its meta data like id, delay and expiration date.

public interface IErrorHandler<T>

{

void Handle(Exception exception, Message message);

}

public class ErrorHandler<T> : IErrorHandler<T>

{

public void Handle(Exception exception, Message message)

{

throw exception;

}

}

Putting all these components to work together, we end up with a queue consumer. When a queue consumer is started, it instantiates a timer which will try to get a raw message from the queue on each tick. If there’s a raw message, it will extract the body, deserialize it into the message, dispatch it, and finally delete the raw message from the queue. If something goes wrong here, the error handler will be invoked, and the message will automatically return back to the queue.

public interface IQueueConsumer<T> : IQueueConsumer where T : class

{

}

public interface IQueueConsumer : IDisposable

{

void Start();

}

public class QueueConsumer<T> : IQueueConsumer<T> where T : class

{

private readonly IQueue<T> _queue;

private readonly IErrorHandler<T> _errorHandler;

private readonly IQueueConsumerConfiguration<T> _queueConsumerConfiguration;

private readonly IMessageDispatcher _messageDispatcher;

private Timer _timer;

public QueueConsumer(

IQueue<T> queue,

IErrorHandler<T> errorHandler,

IQueueConsumerConfiguration<T> queueConsumerConfiguration,

IMessageDispatcher messageDispatcher)

{

_queue = queue;

_errorHandler = errorHandler;

_queueConsumerConfiguration = queueConsumerConfiguration;

_messageDispatcher = messageDispatcher;

}

public void Start()

{

_timer = new Timer((x) =>

{

var message = (Message)null;

var messageBody = (T)null;

try

{

if (!_queue.TryGet(out message))

return;

messageBody = (T)JsonConvert.DeserializeObject(

message.Body, typeof(T));

_messageDispatcher.Dispatch<T>(messageBody);

_queue.Delete(message.Id);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

_errorHandler.Handle(ex, message);

}

}, null, 0, _queueConsumerConfiguration.PollingInterval);

}

public void Dispose()

{

if (_timer == null)

return;

_timer.Dispose();

}

}

Since we have multiple queues to pull from, we can use a queue host to control multiple queue consumers at once. The queue host configuration decides which queue consumer to instantiate and start.

public class QueueHostConfiguration

{

public QueueHostConfiguration(IEnumerable<Type> messageTypes)

{

Guard.ForNull(messageTypes, "messageTypes");

MessageTypes = messageTypes;

}

public IEnumerable<Type> MessageTypes { get; private set; }

}

public class QueueHost : IDisposable

{

private readonly IKernel _kernel;

private readonly QueueHostConfiguration _configuration;

private readonly List<IQueueConsumer> _consumers;

public QueueHost(IKernel kernel, QueueHostConfiguration configuration)

{

_kernel = kernel;

_configuration = configuration;

_consumers = new List<IQueueConsumer>();

}

public void Start()

{

foreach (var messageType in _configuration.MessageTypes)

{

var queueConsumerType = typeof(IQueueConsumer<>).MakeGenericType(messageType);

var queueConsumer = (IQueueConsumer)_kernel.Get(queueConsumerType);

_consumers.Add(queueConsumer);

queueConsumer.Start();

}

}

public void Dispose()

{

if (_consumers == null)

return;

foreach (var consumer in _consumers)

consumer.Dispose();

}

}

In your application, you’ll end up doing something like this to start the queue host.

using (var host = new QueueHost(kernel, new QueueHostConfiguration(

new[] { typeof(MyMessage) })))

{

host.Start();

Console.ReadLine();

}

All the components are glued together using Ninject and some conventions.

public class Bootstrapper

{

public void Run(IKernel kernel)

{

kernel.Bind(x => x

.FromThisAssembly()

.SelectAllClasses()

.InheritedFrom(typeof(IMessageHandler<>))

.BindAllInterfaces());

kernel.Bind<Infrastructure.IMessageDispatcher>()

.To<Infrastructure.MessageDispatcher>()

.InTransientScope();

kernel.Bind(x => x

.FromAssemblyContaining(typeof(IQueue<>))

.SelectAllClasses()

.InheritedFrom(typeof(IQueue<>))

.BindAllInterfaces()

.Configure(y =>

{

y.WithConstructorArgument("projectId", z => { return "your_project_id"; });

y.WithConstructorArgument("token", z => { return "your_token"; });

}));

kernel

.Bind(typeof(Infrastructure.IQueueConsumer<>))

.To(typeof(Infrastructure.QueueConsumer<>));

kernel

.Bind(typeof(Infrastructure.IQueueConsumerConfiguration<>))

.To(typeof(Infrastructure.QueueConsumerConfiguration<>));

kernel

.Bind(typeof(Infrastructure.IErrorHandler<>))

.To(typeof(MyErrorHandler<>));

}

}

This is what I got for now. Next step is to do some more serious integration testing, and see what gives. There are two things I already kind of expect to run into; the maximum number of concurrent connections, and thread starvation (each timer tick starts a new thread). Anything else I’m going to run into?

The biggest disadvantage of opting for pull that is already obvious now, is the possible number of wasted HTTP requests. You could increase the polling interval, and thereby lower the number of requests, but this would harm the throughput of message bursts. Something I’m considering right now, is introducing a smart polling algorithm. Another option that will lower the number of requests, is to pull batches instead of single messages from the queue. Implementing this one will be rather straightforward, yet improve things considerably.