From human decisions, to suggestions to automated decisions

I’ve been wanting to share this experience for a while, but it took me a while to come up with a story and example I could use in a blog post.

I help out during the weekends in a small family run magic shop. I’m the third generation working in the shop. My great-grandfather always hoped that his only son would follow in his footsteps as a carpenter. But at only eighteen years old, my grandfather said goodbye to the chisels and sawdust, and set out for the big city to chase his dream of becoming a world class magician. The first few years were tough, he was no Houdini. He would (hardly) get by performing at kid birthday parties, weddings and store openings. That’s how he met my late grandmother. She worked as a shop girl in one of the first malls that were built in the city, and happened to show up each time my grandfather performed in one of the stores. After getting married, having a baby (my dad) and saving every dime they earned, my grandfather was able to rent a hole in the wall and open up his own tiny magic shop - in that same mall. Once my dad finished school, he worked as a middle school teacher for a few years, giving up on that job to join his father in the family business. He loves to tell you how he can now still teach children, without the chore of grading their homework. I’ve been running around and helping out in the store since I could barely walk. I guess you can say that magic runs in our blood.

Since the beginning of time, our trade has relied on secrecy. However, due to the rise of the internet, magic is dying a slow death. Even the greatest of tricks and illusions are challenged and destroyed in the open by non-believers. Our craft is now reduced by many to a cheap fairground attraction.

My grandfather, even after suddenly losing grandma last year, isn’t willing to give up on the business though. “There will be a time when the people need magic once more, and we will be waiting right here.” He decided not to see modern technology as the nemesis of magic, but rather as a potential assistant.

Instead of fiddling in his study all night with a book of cards, a hat, a scarf and the lonely rabbit, I’ve been working with him trying to show him what happened in technology over the last 30 years. Being a programmer, I started by showing off some of my unfinished hobby projects experimenting with micro controllers. I hadn’t gotten much further than making some LEDs blink controlled by my voice, but that was enough to spark my grandfather’s creativity. “Can that chip make the lights go out? Can it blow smoke? Can it sense if I flip it around real fast?” One evening, tired after brainstorming and testing ideas all night, he told me “being able to tell these little computers what to do might not be magic, but a miracle”.

I would like to tell you the details of what we came up with, but I’d have to make you disappear after I did. To make a long story short, it was an overwhelming success. Neighbourhood magicians picked it up, and even mere mortals thought it was a great gimmick they could show off with. A friend of mine even told me he used our invention to pick up girls. It wasn’t for long before I got daily emails and tweets from all over the world, begging me to ship our gadget their way.

Thanks to some lovely open source software, I was able to set up a full blown web shop in a matter of days. While orders started rolling in, we got a grip on how to actually produce our new product at a sufficient pace. Shipping overseas turned out to be surprisingly easy. What we didn’t anticipate for was how to handle returns and refunds.

This is where the actual story starts…

When our usual customers visit the store, we take our sweet time to show them how to perform the trick. This results in us knowing our customers pretty well and hardly ever having anyone return an item or ask for a refund. Admittedly, growing the same connection with our customers online hasn’t been a success. A lot of them lack the magician mindset. You can’t just buy magic, you have to put the practice in to make the magic happen. These maladjusted expectations make for quite a few phoney complaints.

Me, my dad and my grandfather in turn have been performing the chore of handling returns and refunds. This domain of the open source shop is very much underdeveloped. Even something as simple as looking up a customer’s details and order history, requires scanning multiple pages of information or even querying the database by hand. Making a well-informed decision takes up way more time than it should.

A use case specific view

The first thing I did in an attempt to speed up this process was building a use case specific view. I asked my dad and grandfather which heuristics they use and which data is needed to feed those heuristics. To get the full picture as soon as possible, I imposed the rule that only this specific view can be used to make a decision. If a piece of data was lacking, I would add it the same day.

This process was more useful than I expected. What we learned is that we all used different heuristics, but were also victim to different biases. For example, I learned that my grandfather used to have a Dutch neighbour who would leave for work very early, and slam the door so loud, it woke my grandfather up each morning. He has grown a disliking for the Dutch ever since. When customers were Belgian, he would much more lean towards issuing a refund, since he believes Belgians are less likely to lie about the cause of a broken item. We also discovered that we used different words for specific numbers. I would use “Items purchased sum”, but my dad would use “Items purchased lifetime” to define the total amount of money spent purchasing items. We decided on being more explicit and making a composition of all those words.

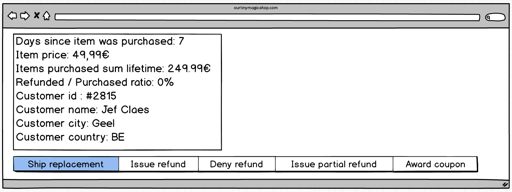

I ended up with a simple screen that rendered a read model that looked something like this.

type ReadModel = {

DaysSinceItemPurchased : int

ItemPrice : decimal

ItemPurchasedSumLifetime : decimal

RefundedToPurchasedItemsRatio : decimal

CustomerId : string

CustomerName : string

CustomerCity : string

CustomerCountryCode : string

}

Based on heuristics in the head and a snapshot of information available in the world, we would make a decision and click a button to execute a specific command.

type Command =

| IssueRefund

| IssuePartialRefund

| AwardCoupon

| ShipReplacement

| DenyRefund

| DeferDecision

type Snapshot = {

SnapshotId : string

Value : ReadModel

}

type Decision = {

BasedOnSnapshotId : string

Command : Command

MadeBy : string

}

type MakeDecision = Snapshot -> Decision

let makeHumanDecision by : MakeDecision =

// Heuristics in the head, fed by knowledge in the world

fun snapshot ->

{

BasedOnSnapshotId = snapshot.SnapshotId

Command = IssueRefund

MadeBy = by

}

Making suggestions

By now, I had gotten quite interested in this domain. Each day I would go over all of the decisions and see whether I understood why a decision was made. I would call the shop each time I didn’t understand and scribble down notes whenever I discovered a new implicit rule. In the meanwhile, I started experimenting with codifying these rules to make automated decisions, but when I ran the older snapshots through my routine the results were not 100% there yet. Instead of making automated decisions, I switched to making suggestions instead.

type Suggestion = {

Command : Command

Confidence : int

}

type Suggestions = {

BasedOnSnapshotId : string

Options : Suggestion seq

}

type MakeSuggestion = Snapshot -> Suggestions

let machineMakesSuggestions snapshot =

let returnWindowInDays = 14

let itemInReturnWindow = snapshot.Value.DaysSinceItemPurchased <= returnWindowInDays

let options =

if itemInReturnWindow then

[

{ Command = ShipReplacement; Confidence = 51 }

{ Command = IssueRefund; Confidence = 49 }

{ Command = DenyRefund; Confidence = 0 }

{ Command = AwardCoupon; Confidence = 0 }

{ Command = IssuePartialRefund; Confidence = 0 }

]

else

[

{ Command = DenyRefund; Confidence = 50 }

{ Command = AwardCoupon; Confidence = 30 }

{ Command = IssuePartialRefund; Confidence = 10 }

{ Command = ShipReplacement; Confidence = 10 }

{ Command = IssueRefund; Confidence = 0 }

]

{ BasedOnSnapshotId = snapshot.SnapshotId; Options = options }

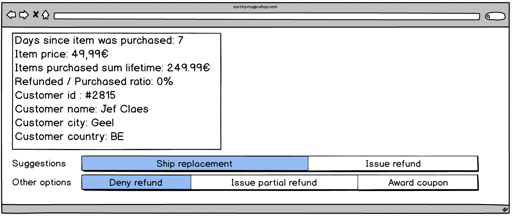

I rendered these suggestions on top of the existing view and observed the decisions that were made.

type PickSuggestion = Suggestions -> Decision

let humanPicksSuggestion by : PickSuggestion =

fun suggestions ->

{

BasedOnSnapshotId = suggestions.BasedOnSnapshotId

Command = IssueRefund

MadeBy = by

}

My partners in crime were quite ecstatic with this new feature. They had a bit more room to breathe and could spend more time doing things they liked.

After observing and comparing the suggestions with the decisions made, I kept tweaking the routine a bit more. I got close but I felt as if I wasn’t quite there yet.

Automating decisions

It was my grandfather who eventually pushed me to fully automate making these decisions. He said “I almost always find myself picking the first option. It’s fine if the machine is a bit off now and then. Just defer decisions and call in a human when the machine is not confident enough.” How can I question my grandfather’s wisdom? And so this happened…

let machinePicksSuggestion : PickSuggestion =

fun suggestions ->

let confidenceTreshold = 50

let command =

suggestions.Options

|> Seq.filter (fun x -> x.Confidence >= confidenceTreshold)

|> Seq.sortByDescending (fun x -> x.Confidence)

|> Seq.map (fun x -> x.Command)

|> withFallbackTo DeferDecision

|> Seq.head

{

BasedOnSnapshotId = suggestions.BasedOnSnapshotId

Command = command

MadeBy = "Machine"

}

From human decisions, to suggestions, to automated decisions

With that, we’ve come full circle. I’m happy to report that my dad, grandfather and I are back to spending more time in my grandfather’s study coming up with new tricks.

I regularly have a look at the data to check for anomalies and to tweak the routine a bit further. But even that is taking up less and less time. To be fair, I didn’t invest in a full blown test suite even though this small routine has grown into 200 lines of code. I find much relief in the fact that when I replay past decisions, I hardly ever find a regression.

Maybe if we invent another popular trick like this one, we will acquire enough data to let the machine do the learning for me. For now, it’s automagical enough.